Motion to Purchase Wigs Approve

Written by Kim van Alkemade

In July 2007, I was doing family research at the Center for Jewish History in New York City, sifting through some materials I’d requested from the American Jewish Historical Society archives. The idea of writing a historical novel was the furthest thing from my mind when I opened Box 54 of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum collection and began leafing through the meeting minutes of the Executive Committee.

The minutes gave intimate glimpses into the day-to-day operations of an orphanage that, in the 1920s, was one of the largest child care institutions in the country, housing over 1,200 children in its massive building on Amsterdam Avenue. On October 9, 1921, the Committee authorized $200 (over 2000 in today’s dollars) to costume children for the “Pageant on Americanization.” The question of band instruments demanded much of the Executive Committee’s attention: in October 1922, the decision to change from high to low-pitched instruments was deferred; in April 1923, $3500 was approved to equip the band with low-pitched instruments; in January 1926, the theft of the new band instruments was referred to the Board. Syphilis was a concern, too, with the Committee instructing the Superintendent in January 1923 to work with the physician regarding syphilitic cases; by October 1926, nineteen cases of syphilis were diagnosed in the orphanage, fourteen of them in girls. My description of the X-ray room at the Hebrew Infant Home was inspired by this 1919 photograph of the X-ray room at Vancouver General Hospital—where no medical research involving children was conducted.

My description of the X-ray room at the Hebrew Infant Home was inspired by this 1919 photograph of the X-ray room at Vancouver General Hospital—where no medical research involving children was conducted.

But it was a motion made on May 16, 1920 that caught my eye and became the inspiration for Orphan #8. On that day, the Committee approved the purchase of wigs for eight children who had developed alopecia as a result of X-ray treatments given them at the Home for Hebrew Infants by Dr. Elsie Fox, a graduate of Cornell Medical School. Questions cascaded through my mind. Who was this woman administering X-rays? Why did the orphanage have an X-ray machine, and what were the children being treated for? What might have happened to one of these bald children after she had grown up in the orphanage? How would this have influenced the course of her life?

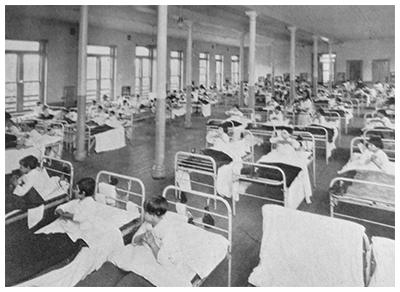

I remembered then a story my great-grandmother, Fannie Berger, used to tell about her time working as Reception House counselor in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. She’d been hired by the Superintendent in January 1918 when she went to the orphanage to commit her sons to the institution after her husband had absconded. One of Fannie’s jobs was to shave the heads of newly admitted children as a precaution against lice. It was a task she disliked, but refused only once. Rachel's dormitory in the Orphaned Hebrews Home was inspired by this photograph of a dormitory in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum.

Rachel's dormitory in the Orphaned Hebrews Home was inspired by this photograph of a dormitory in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum.

We used to drive out to Brooklyn when I was little, my mom and dad and brother and me, to visit my Grandma Fannie. We’d often find her on a bench outside her building, chatting with other old ladies. Up in her tiny apartment we’d perch uncomfortably on the day bed while we visited—I can’t imagine, now, a child with the patience for such an afternoon. I remember Fannie telling a story about the time a girl with beautiful hair was committed to the orphanage. It may be my imagination rather than my memory that makes this particular head of hair so remarkably red. Fannie was so taken with this girl’s hair that she refused to shave it off, took her request all the way up to the Superintendent who finally gave permission. In my Grandma Fannie’s telling, it was a singular moment of bravery, her refusal to shave this one girl’s head of hair. The Hebrew Orphan Asylum baseball team. My grandfather, Victor, is seated in front of his brother Seymour, the team's “pillar of strength.”

The Hebrew Orphan Asylum baseball team. My grandfather, Victor, is seated in front of his brother Seymour, the team's “pillar of strength.”

At the Center for Jewish History, reading about the children who had been given X-ray treatments, I wondered what if, at the same time these bald children were in my great-grandmother’s care, this other girl came into Reception, the girl with hair so magnificent Fannie would challenge authority to preserve it? I imagined the contrast between these two girls escalating into a rivalry, the hair itself becoming their battleground. That was the moment Rachel and Amelia were created, and with their inception the idea of a novel began to emerge.