Ever Efficient Boy of the Home

Written by Kim van Alkemade

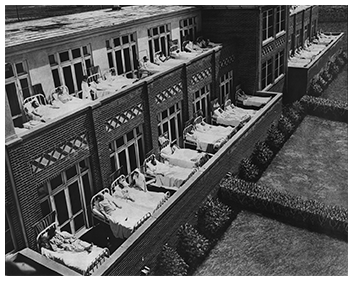

Even before my discoveries at the Center for Jewish History, I’d wanted to learn all I could about the institution where my grandfather Victor had grown up—an institution so large it was its own census district. I’d read The Luckiest Orphans, the most complete history of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum ever written, and was so appreciative of the insight it gave me into my grandfather’s childhood that I wrote the author, Hyman Bogan, a letter of thanks. Apparently, he wasn’t used to getting fan mail. I was amazed when I answered my phone one evening in 2001 to hear a strange man’s voice say, “Is this Kim? You wrote to me about my buh-buh-buh-book.” Hy later told me his stutter had began after being slapped on his first day in the orphanage.

I asked if I might meet him in New York for an interview and he was delighted at the prospect. Together we toured Jacob Schiff Playground, the public park on Amsterdam Avenue where the massive orphanage once stood. Much of my fictional depiction of life in the Orphaned Hebrews Home was inspired by Hy’s words and memories. Thanks to him, I was able to imagine Rachel’s life in an orphanage, from clubs and dances to loneliness and bullying.

My research suggests that my grandfather Victor flourished at the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. By the time he was a high school senior, he was a salaried captain—a position just below counselor—as well as vice-president of the Boys’ Council, a member of the Masquerade Committee, secretary of the Blue Serpent Society, and a member of the varsity basketball team. He was “the hustling young business manager” for The Rising Bell, the orphanage’s monthly magazine. Upon his graduation from DeWitt Clinton School, Vic was praised for his “stick-to-it-iveness” and “pleasant personality.” A “brilliant future in the outside world” was predicted for this “ever-efficient boy of the Home.” Though he rarely spoke of his childhood in the orphanage, he did express his gratitude for the institution in which he lived from age 6 to 17.

But I knew there was another side to Victor’s childhood memories. In 1987, my dad had gone missing; for two months, we’d had no inkling of his whereabouts. When Victor said, “I want to talk to you about your father,” I was expecting the same optimistic platitudes I’d been hearing for weeks: that everything would turn out fine, how brave I was, how strong. I couldn’t have been more mistaken. “Your father left you. You just forget about him from now on.” I knew Victor’s attitude was misplaced—if we were sure of anything, it was that my dad hadn’t run away to start a new life somewhere else—but my grandfather had gotten my attention. “My father left us, too, when me and my brothers, your uncles Seymour and Charles, were just little boys.’ I understood now. Victor was offering me advice, one orphan to another, on how a child gets through life without a father: just forget about him.

“We got a letter from my father once, did you know that?” This was news to me. I’d always assumed my great-grandfather had vanished, whereabouts unknown. Until I started researching my family history, I didn’t even know his name. “When your Grandma Fannie worked at the Reception House in the orphanage, we used to visit her on Sundays, me and my brothers. One time, she read us this letter she’d gotten, from California, that our father was sick and would we send money for his treatment. She asked us boys what should she do. We told her not to send him a dime. A few months later she got another letter saying that he died, and would we send money for a headstone. Me and my brothers, we said no. He left us, like your dad left you. We didn’t owe him a thing, and neither do you. Remember that.”

What amazed me more than the revelation of the letters was Victor’s anger. It radiated off him, like heat rising over asphalt. Seventy years had elapsed and still he was mad at his father for making him an orphan. In April, the melting snows would expose my father’s body, revealing that I was the daughter of a suicide, the outcome I’d suspected all along. Surely, that was different from the way Harry Berger had left his family? But however they left us, Victor and I were both children abandoned by their fathers.

Instead of following my grandfather’s advice to forget, however, I became intensely curious to know more. I began researching my family history, learning all I could about Harry Berger, the man who left his wife to commit their sons to the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. Eventually, that research led to the discoveries that inspired me to write Orphan #8.