Contractor of Waists

Written by Kim van Alkemade

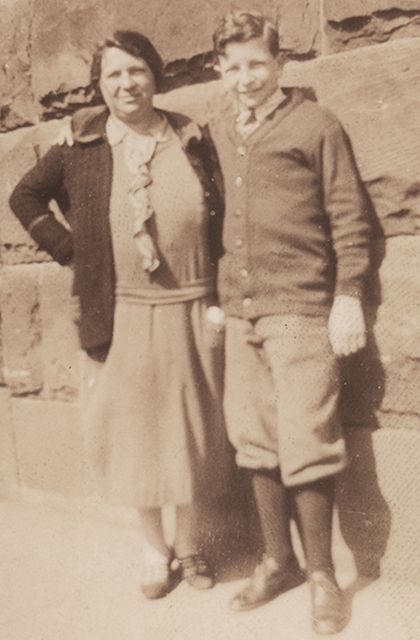

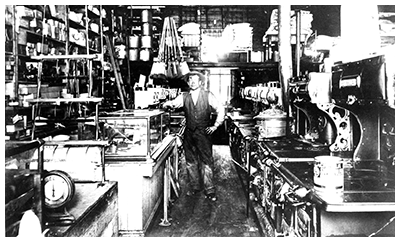

There is some mystery to the disappearance of my great-grandfather, Harry Berger, a contractor in the shirtwaist industry who’d been born in Russia in 1884 and arrived in New York in 1890. On the admission form to the orphanage, it is remarked that “Father is tubercular and is at present in Colorado with his brother,” which gives the impression that illness and the inability to work were behind Harry’s decision to leave his wife and three young sons. But the story I remember hearing is that Harry had gotten a young Italian woman who worked for him pregnant; when her family threatened to kick her out, Harry asked his wife if the girl could live with them. Fannie refused, but she hadn’t been prepared for Harry to up and leave. Decades later, suffering from dementia, Fannie relived the day he left, pleading from her nursing home bed to the ghost of her husband: “Don’t leave, Harry. Think of the boys. Put back the suitcase, we’ll get through this.”

They didn't get through it. Harry ran off to Leadville, Colorado. Fannie couldn't go home to her parents because she’d defied her father in marrying Harry—unlike Fannie’s obedient sister, who’d been married off by their father to a rich uncle. After Harry left, Fannie sold her household effects for a total of $60. She might have turned, in desperation, to prostitution—many abandoned mothers occasionally did—or tried to eke out an existence on charity. Instead, she went to the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, like thousands of parents before her, who, for reasons of death or desertion or illness, were unable to care for their children.

Like many inmates of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, my grandfather Victor and his brothers, Charles and Seymour, were not really orphans, and certainly not up for adoption. What was unusual was that their mother ended up living at the institution to which she had committed them. In 1918, the orphanage was experiencing a serious shortage of help. With so many men in the military, women had greater employment opportunities, making jobs at the orphanage—with its low wages, long hours and residence requirement—a hard sell. While Fannie always said it was a miracle that the Superintendent offered her a position on the very day her sons were admitted to the institution, it’s also true that her poverty and desperation to be near her children made her an ideal candidate.

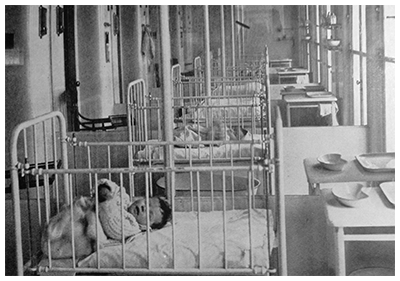

When Fannie started working at the orphanage as a domestic in the Reception House, Charles was only three years old—too young for the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. He was sent to the Hebrew Infant Asylum, where he soon contracted measles. When Fannie went to visit him, she wasn’t allowed into the ward and could only stand in the hallway listening to his cries. When Charles recovered, Fannie threatened to quit unless her son was allowed to live with her in the Reception House. After Charles was old enough to join his brothers in the main building, Fannie was promoted to Counselor and her duties included helping to process new admissions. Every child committed to the orphanage spent weeks quarantined in Reception. Besides having their heads shaved, they were evaluated by a doctor for physical and mental condition, tested for diphtheria, vaccinated, and given an eye test and a dental exam and surgery to remove the tonsils and adenoids. My great-grandmother Fannie often let the traumatized children cry themselves to sleep at night in her arms.