A Wall They Cannot See

Written by Kim van Alkemade

Joan Nestle, co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, came to Milwaukee, while I was in graduate school there, to give a lecture. She read to us from a letter given to the archives by a woman who had endured the humiliation and fear of a police raid on a lesbian club in the 1950s. When I imagined Rachel and Naomi’s relationship, at first I thought no further than their romantic reunion at the carousel. But as I developed the novel, I realized how important it would be to explore the ways in which the characters would have responded to the repressive era in which they lived. As a lesbian writing at the time explained, “Between you and other women friends is a wall which they cannot see, but which is terribly apparent to you. The inability to present an honest face to those you know eventually develops a certain deviousness which is injurious to whatever basic character you may possess. Always pretending to be something you are not, moral laws lose their significance.”

In the 1950s, psychiatry in America purported that homosexuality was a psychological disorder that could be cured through analysis and therapy. The prevailing scientific view, as expressed by Dr. Frank Caprio in Female Homosexuality: A Psychodynamic Study of Lesbianism (New York: Citadel Press, 1954) was that homosexuality resulted from “a deep-seated and unresolved neurosis.” Caprio explained, “Many lesbians claim that they are happy and experience no conflict about their homosexuality, simply because they have accepted the fact that they are lesbians and will continue to live a lesbian type of existence. But this is only a surface or pseudohappiness. Basically, they are lonely and unhappy and are afraid to admit it, deluding themselves into believing that they are free of all mental conflicts and are well adjusted to their homosexuality.”

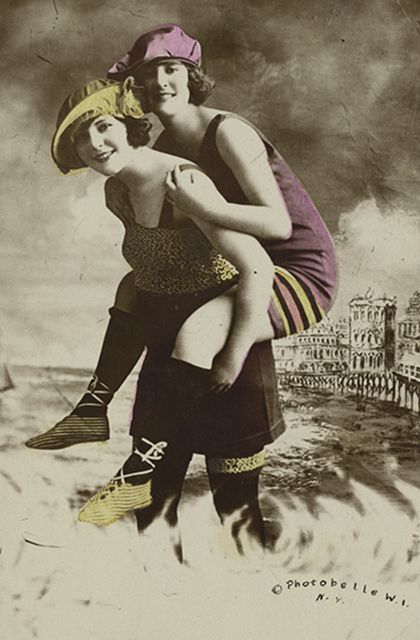

As adults, Rachel and Naomi would have lived with the dual experience of their relationship being both invisible (as female spinster roommates) and dangerous. Lesbian teachers and nurses in particular were fearful of losing their jobs and reputations. Living in the Village would have helped to ease their sense of isolation. As Caprio helpfully notes, “The Greenwich Village section of New York City has for many years been known as a center where lesbians and male homosexuals tend to congregate, particularly those with artistic talent.” But when Naomi’s Uncle Jacob offers them his apartment rent-free, the move out to Coney Island exacerbates their sense of isolation.

The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society would have been one group where homosexuality was not condemned. Sigmund Freud’s 1909 visit to Dreamland, Luna Park and Steeplechase Park led him to confide to his diary that the “lower classes on Coney Island are not as sexually repressed as the cultural classes.” Freud’s visit to Coney Island was the inspiration for the 1926 formation of the Amateur Psychoanalytic Society, which met monthly and hosted an annual Dream Film award night—home movies which dramatized significant dreams and presented the dreamer’s accompanying analysis. One of them, “My Dream of Dental Irritation” by Robert Troutman, openly explores a gay theme. According to Zoe Beloff, editor of The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and Its Circle (New York: Christine Burgin, 2009), “Troutman says he was drawn to the Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society as a teenager struggling to come to terms with his homosexuality.”

As adults, Rachel and Naomi would have lived and worked in a society that denigrated and maligned their sexuality. In the orphanage, however, the atmosphere may have been more permissive. One man, recalling his years at the Hebrew Orphan Asylum in response to a survey, matter-of-factly observed, “As far as homosexuality was concerned, I think there was plenty of it going around. In my own case, I jerked off quite a few fellows, and they did likewise to me.” For girls, intense crushes—including love notes, jealous intrigues, and displays of affection—were common, though these relationships were widely understood as immature substitutes for the heterosexual attractions that were expected to eventually replace them. Unless, of course, the girls bravely chose to live “a lesbian type of existence.”